Surprising fact: up to 40% of patients report much less pain after targeted regional techniques following inguinal surgery.

This introduction explains what a focused ilioinguinal nerve block is and why clinicians use it. The technique targets small abdominal nerves that arise from the L1 level of the spine and run between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles near the anterior superior iliac spine.

With modern ultrasound guidance, clinicians can see the muscle layers and the fascial plane where a safe volume of local anesthetic spreads. Color Doppler helps avoid the deep circumflex iliac artery and reduces risks like accidental peritoneal entry.

Benefits include targeted anesthesia for hernia repair, better postoperative analgesia, and less systemic medication for the patient. The section that follows will cover anatomy, ultrasound technique, safety checks, and recovery tips.

Key Takeaways

- Targets L1-origin nerves that travel in a plane between key abdominal muscles.

- Ultrasound and color Doppler improve accuracy and reduce vascular or peritoneal risks.

- Typical adult volumes spread 10–20 mL of local anesthetic in the fascial plane.

- Used for postoperative analgesia after inguinal hernia repair and for groin pain.

- Overlap with nearby nerves may require combined blocks for full coverage.

What is an ilioinguinal nerve block and who can it help?

This procedure aims to place local anesthetic in a tight tissue plane to produce reliable sensory relief across the groin.

What it does: An ilioinguinal nerve block is a targeted regional anesthesia that numbs pain pathways from the lower abdomen into the groin and genital area. It serves diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic roles for persistent groin and genital pain.

Who benefits: Patients with burning pain, tingling, or paresthesias that radiate to the scrotum, labia, or upper inner thigh often find relief. The technique is used for hernia surgery and non‑surgical pain care in adults and children, with doses adjusted by size.

- Clinicians may combine this with an iliohypogastric nerve or genitofemoral block for broader surgical anesthesia.

- Ultrasound guidance improves accuracy and lowers complication rates versus landmark-only approaches.

- Small volumes of local anesthetic placed between two muscles focus relief and limit systemic drug exposure.

Key anatomy and indications: ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric pathway and pain targets

Mapping L1 branches shows how predictable anatomical routes make targeted pain control possible.

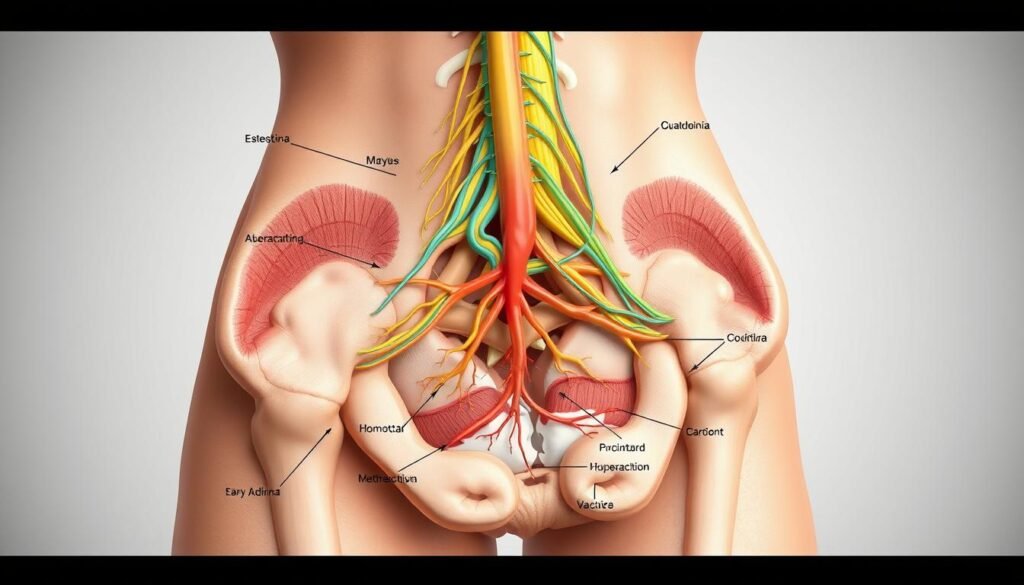

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric fibers arise from L1 of the spine and cross the posterior abdomen. They pass anterior to quadratus lumborum and iliacus, then pierce the transversus abdominis near the iliac crest.

Near the anterior superior iliac landmark the fibers travel between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis. This fascial plane is the primary target for a precise plane injection using ultrasound guidance.

Sensory territory and overlap

The sensory distribution covers the lower abdomen, upper medial thigh, and genital skin such as scrotum or labia. Individual patterns vary because of overlap with the genitofemoral pathway.

When clinicians choose this approach

- Postoperative analgesia after inguinal hernia repair to reduce opioid needs.

- Treatment for chronic groin or genital pain and diagnostic use in ilioinguinal neuralgia.

- Combined approaches when adjacent nerves cause incomplete coverage.

Practical point: scanning above the superior iliac spine toward the inguinal canal lets the operator confirm the fascial plane and plan a safe needle trajectory. Modest local anesthetic volumes then spread where the fibers run together.

Preparation essentials: positioning, landmarks, and equipment

Clear setup reduces surprises and speeds safe performance.

Position the patient supine, expose the lower abdomen and iliac crest, and identify the anterior superior iliac spine to draw a straight ASIS–umbilicus guidance line.

Probe and imaging: use a high-frequency linear ultrasound transducer (10–12 MHz) placed obliquely just superior and medial to the ASIS. Set depth to roughly 1–3 cm so the internal oblique and transversus abdominis come into crisp view and the thin fascial plane is visible.

Needle and dosing: select a 21–22G needle, 50–100 mm for comfortable in‑plane control and needle tip visualization. Prime color Doppler to detect nearby vessels. Plan ~10 mL of local anesthetic per side (adjust per clinical goal), or 10–20 mL total within the plane for adults.

Prepare a sterile field, syringes for test and main injection, gel, and sterile covers. Mentally rehearse probe orientation, muscle ID, and a steady in‑plane approach. Confirm the patient understands monitoring and postprocedure expectations.

Ilioinguinal nerve block: step-by-step ultrasound-guided technique

Begin with a clear image before advancing the needle. Place the linear transducer obliquely along the ASIS-to-umbilicus line, with the inferior edge over the anterior superior iliac landmark. Slide and tilt until the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle layers are in crisp view and the bright fascial plane between them is visible.

Identify the small ovoid hypoechoic targets sitting within or adjacent to that plane. Trace these structures gently along the plane to confirm their course toward the inguinal canal.

Needle approach and hydrodissection

Use an in-plane technique so the needle runs parallel to the ultrasound beam. Advance a 22G needle slowly, keeping continuous visualization of the needle tip. Pause to confirm the tip is above the peritoneum and beneath the abdominis muscle layer of interest.

If the plane resists entry, inject 1–2 mL to hydrodissect and separate tissues. Watch for laminar separation; intramuscular spread looks patchy and signals repositioning by 1–2 mm.

Injection, spread, and confirmation

After correct placement, inject a diagnostic 5 mL or a therapeutic 10–20 mL of local anesthetic while watching for even expansion between the muscles.

“Confirm correct spread by the downward bowing of the transversus abdominis and a smooth expansion in the fascial plane.”

Keep color Doppler on intermittently to avoid the deep circumflex iliac artery. Document the local anesthetic injected and the final sonographic appearance for reproducibility. For an illustrated procedural review see an ultrasound-guided technique review.

| Step | Key action | Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Probe placement | Oblique on ASIS–umbilicus line | Inferior edge over anterior superior iliac |

| Localization | Identify internal oblique and transversus abdominis with bright fascial plane | Trace ovoid hypoechoic targets |

| Needle | In-plane 22G, track tip continuously | Hydrodissect 1–2 mL if needed |

| Injection | 5 mL diagnostic; 10–20 mL therapeutic | Look for downward bowing of transversus abdominis |

| Safety | Use color Doppler, avoid intramuscular spread | Document volumes and sonographic spread |

Safety, risks, and how ultrasound improves outcomes

Visualizing tissue planes in real time reduces the chance of advancing the needle into the peritoneal cavity. Ultrasound draws a clear boundary between the transversus abdominis and the peritoneum so the operator keeps the needle tip in the safe fascial plane.

Key safety steps

- Use ultrasound to map the abdomen and confirm the internal oblique and abdominis layers before advancing the needle.

- Apply Color Doppler to locate the deep circumflex iliac artery and avoid vascular contact.

- Advance the needle slowly with continuous tip visualization; gentle hydrodissection separates the plane when needed.

Partial or failed results often come from depositing local anesthetic inside muscle instead of the plane. Small test aliquots and incremental injection with frequent aspiration lower intravascular risk and improve spread.

After withdrawal, apply brief pressure to the skin to reduce ecchymosis, especially for patients on antiplatelet therapy when policy allows. Document the needle path, tip position, and sonographic spread; this supports quality care and future nerve blocks.

Benefits, results, and recovery for patients in the United States

Many patients notice a steady reduction in groin pain within an hour after a properly placed regional injection. This targeted approach often reduces opioid needs after hernia repair and supports earlier walking and discharge.

Analgesia for hernia repair and targeted relief

Effective postoperative pain control follows when local anesthetic spreads in the fascial plane that covers the hypogastric area, inguinal crease, upper medial thigh, and genital skin.

For patients with groin or genital pain, the procedure gives focused relief that maps well to those sensory zones. Smaller diagnostic injections help confirm the exact source of pain before broader treatment.

Post-procedure care: numbness, mobility, and follow-up

Expect numbness of the skin over the lower abdomen and groin and a sense of warmth as the anesthetic works. These effects are usually temporary.

Most people resume gentle activity the same day. Care teams advise avoiding heavy lifting until sensation and muscle strength return.

- Brief pressure at the injection site can reduce bruising.

- Clinicians monitor for swelling or prolonged numbness and give clear follow-up instructions.

- If relief is short-lived, repeat injections or longer-acting options may be discussed.

“Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia reduces complications and yields more consistent results than landmark-only techniques.”

Conclusion

Conclusion: Precise probe alignment along the anterior superior iliac‑to‑umbilicus line, careful needle tip tracking, and mindful injections let clinicians use smaller volumes of local anesthetic for reliable results.

Ultrasound visualization of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis plane confirms correct local anesthetic injected spread and limits intramuscular deposition that causes partial failures.

Color Doppler adds vascular safety near the deep circumflex iliac artery and the superior iliac spine. Knowledge of spine‑to‑peripheral anatomy supports reproducible technique and helps tailor volumes for diagnostic or therapeutic goals.

For patients, this means focused pain relief, fewer systemic medications, and a faster return to activity. With training and consistent practice, ultrasound‑guided ilioinguinal nerve block remains a dependable option for groin and lower abdominal care.